Building on yesterday’s post on “Managing Expectations,” today’s musings on teaching online are about how and why and when we use technology, what form does that technology take, and the benefits of thinking and doing “low tech.” Riffing on the common sense axiom, “You don’t solve money problems with more money,” I think this is true of technology in the classroom: “You don’t solve technology problems with more technology.” In this case, online teaching is not about more online, more tech but about more teaching.

With concerns over whether or not the digital infrastructure of homes, cities, and nations can handle the sudden surge in broadband demand, over accessibility particularly for students with disabilities and digital divides, and over the further erosion of education, the need to think about low tech, hybrid, even analog alternatives, solutions, and accommodations is real. I am also wary that the amazing work, innovation, creativity, and chutzpah that will emerge from this emergency will be co-opted, homogenized, monetized, and ultimately weaponized against the very teachers, creators, and students that saved the system. Particularly with digital technologies, riffing on Thomas Foster’s “key antimony of posthumanism,” the very technologies used for liberation, democracy, and creation can also be leveraged for control, oppression, and violence. For example, the turn to videoconferencing and telepresence technologies is not only bandwidth gobbling but also introduces other risks and unintended consequences, particularly over privacy and surveillance. (Have we even thought through things like whether or not these technologies are FERPA compliant?)

But enough with the doom and gloom. On to my next ideas and suggestions.

Rule #2: Low Tech is the Best Tech

As I wrote in my previous post: there is no one size fits all technology or solution; careful integration is much harder than superficial inclusion. In my face-to-face classrooms I am decidedly low tech — I use a computer or laptop, I use the Internet and web, I use a small suite of software like word processing, PDF readers, text editors, browsers, presentation programs like Prezi — but for the most part everything else is analog, pen and paper, and embodied (i.e. me, students, texts). Even in my video game studies class, I tend to use older games, web-based games, free-to-play and free-to-download and free-to-try games, and analog games. Moreover, not everything can translate to the digital, to distance learning: I am at a loss as to how my friends and colleagues are going to teach hands-on skills, lab work, fine arts, sports, and so on. I teach a game on live-action role-playing games, which cannot fully be ported to the digital.

It is not that I am against incorporating other technologies and tools into my classroom. I want to, but wishes might be trojan horses. I am slow to adopt because I must need a substantive, medium-specific need for said tech and because I am usually too harried and busy to do a good job at integration. Anyone that has ever tried to set the clock on any device or doodad knows “plug and play” is largely a lie. Again, teaching online requires a lot of front loaded work, and every new bit and bob brought into the class requires set up, testing, framing, training, implementing, maintenance, and reflection. I fear too much of poorly-designed online teaching is about bells and whistles for bells and whistle’s sake.

In many ways, the way I use technology in my face-to-face classrooms and my online courses mirrors my syllabus blurb on students using technology:

Learning (with) Technology

Unless you have an official accommodation, the use of technology in our classroom is a privilege, not a right. Mobile devices like phones, media players, and cameras should be off and put away. Computers and tablets should be used for note-taking, in-class work, and readings only. Print is generally preferred for course texts and readings, but full-size e-versions are acceptable provided the student is able to readily highlight, annotate, and index. Finally, be conscientious and respectful in the use of the course website and social media and post no material from class to the internet or non-class sites without explicit permission from the instructor and the class. Keep in mind these three rules:

1) Use the Right Tool for the situation and the task–keep it simple and elegant,

2) Practice Best Practices–it must improve or enhance your learning,

3) Be a Good Neighbor–it cannot distract or detract from others’ learning.

Inappropriate use and abuse of technology in class will result in the taking away of technology privileges for the offending student and/or class as a whole.

Keeping in line with the “less is less” theme, I think having the fewest possible moving parts makes the rest of the engine of the course run more efficiently, smoothly, and powerfully. The use of the tool or tech should never outshine the reason for its use; medium-specific and tool-specific pedagogy ensures that the implicit, explicit, and metacognitive function of a technology or text are clear to both teacher and students. Especially in the current moment when people want to get classes converted to online or set up courseware quickly, less is better and low tech will be a lifesaver. Therefore, here are my takeaways for teaching online with the “best” tech:

- Use What You Have, Use What You Know: First, take an inventory of what digital (and analog) tools you have at your disposal, what is easy or free to get, and what is already adopted as part of the instructional ecology of your department or university. Then decide what is already well-used, what would easiest or simplest to learn or incorporate, and what is aspirational to be invited into the course at a later time or different term. Limitations can often lead to surprising invention and creativity. Most learning/content management systems are inconsistent and idiosyncratic in what they do well and what they don’t do well, but finding ways to mitigate the problems and take advantage of what works means using a system already in-house and thickening the students’ proficiency and capacity with the LMS, which will transfer to their other courses. If every course used novel and different tools, then at the department or institutional level, there is no feedback loop, no reinforcing of the digital culture and norms across courses. This is not to say that there aren’t reasons for a diversity of technology or disciplinary-specific tools. Rather, there is benefit to building a foundation around already shared and known platforms and tools, and then carefully curating add-ons and other technologies.

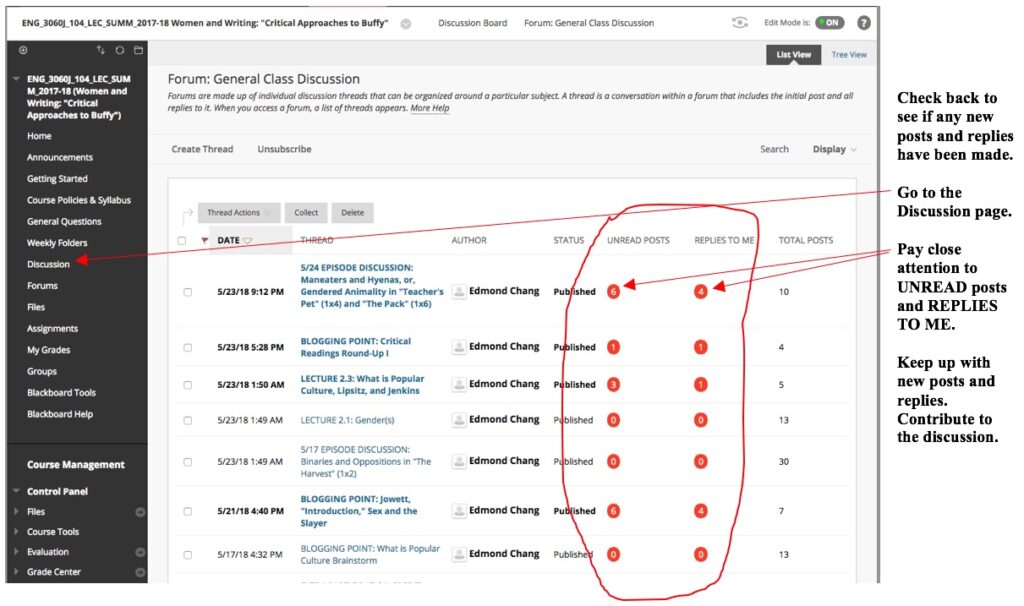

- Digital Proficiency is Learned: Again, no one is a “digital native.” In the setup of my online courses, I have a forum/discussion area/folder specifically for Q&A about the logistics, mechanics, and running of the class itself. There are threads on course policies, on each major assignment, and most importantly, on how to use the technology itself. Using simple edited screen shots, I walk everyone through how to understand what they are looking at, how to post, upload files, embed images and video, and so on. If I am using an outside tool, like Google Hangouts, I create a user guide for that as well. The great thing about all of this preparation is that it can be used over and over again for face-to-face and online courses. Assume everyone is a novice, encourage the sharing of expertise. I encourage students who are comfortable with the technology to help each other often posting a reply, “That is really neat. How did you do that?” or “Where did you find that information?” Moreover, as the instructor, I often affirm that digital proficiency is something I too am working on, that sometimes I am learning alongside the class. Even though I consider myself pretty savvy with technology, I am occasionally surprised by a function, short cut, or solution that a student has shared with the class. Much like the imposter syndrome when it comes to academic writing, particularly in peer review, I think stressing these things are practiced and learned helps assuage those with digital imposter syndrome. Indeed, this extends to faculty and staff as well.

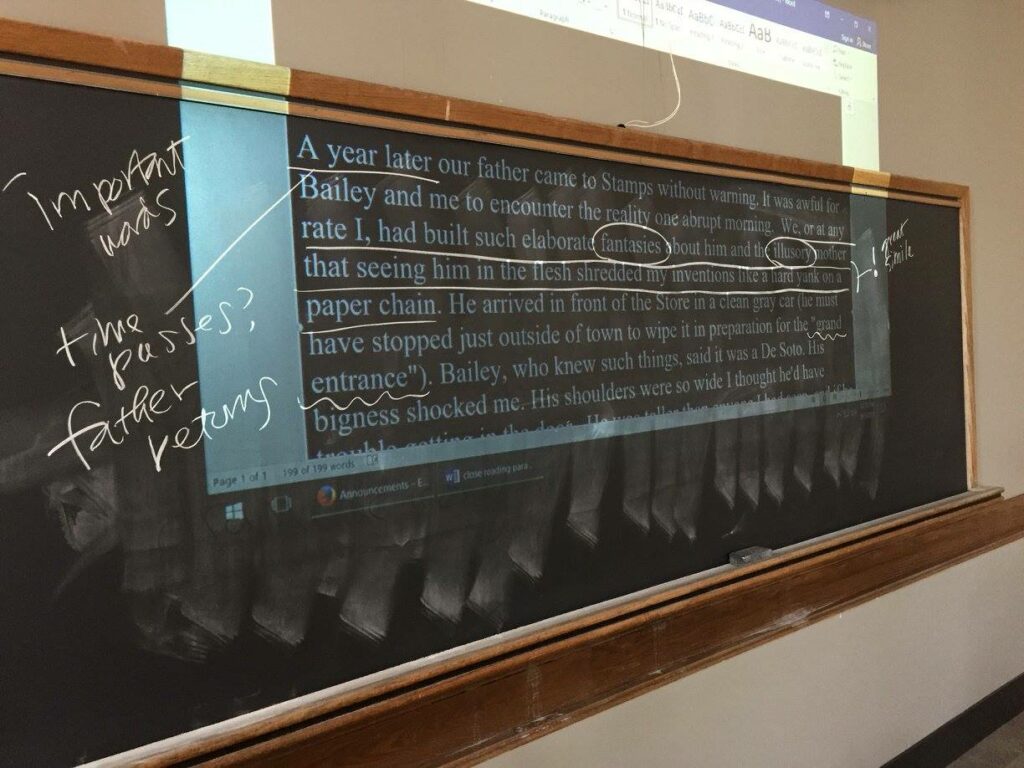

- Use the Right Tool, Keep It Simple, Start Low Tech: Another way of saying this, tongue in cheek, is why use a digital tablet and stylus when a pencil will do? Not everything needs to use yet another tool, not everything needs to be gamified, and not everything needs to be digital. Many times low tech or analog tech is far more efficacious, economical, and accessible, particular those that are already in the institution’s or student’s milieu. I am a big fan of taking notes by hand, marking up books and hardcopy, and paper prototyping. (The above image is me adapting a chalkboard turning it into a “smart” board.) This is not to say I do nothing digitally but that shift and transformation is based on context, circumstances, and accommodations. There are gains and losses depending on medium and method. Teachers and students need to understand these differences so they can use the technology wisely. For example, reading on paper is different than reading on a screen. Moreover, the broader caution here is to be skeptical of one’s own desire to “make it new” or “students will like it better” simply by adding a tool or technology. This is what I have called the interactive fallacy in my own work on video games. I oft cite Salen and Zimmerman’s work on the “immersive fallacy,” the idea that games are supposed to transport the player, that their sensorium will be seamless absorbed into the game world. While games can be engrossing, entertaining, and even instructive, the idea of total immersion is a fantasy and one that is perpetuated and evangelized by players and game companies alike. I have extended the immersive fallacy to talk about the interactive fallacy–the idea that just because games offer feedback to player input does not mean the player has power, control, and choice. In the case of teaching online, we must be wary of the interactive fallacy, the seductions of digitizing and gamifying the classroom. In other words, is there a substantive reason to shift discussion to Twitter, Slack, or Facebook (which mirrors the reason to shift from asynchronous to synchronous teaching)? Is there a critical rationale for asking students to use slides, build websites, make podcasts, play games, or code? Is there a medium- or tool-specific benefit to peer reviewing via Google Docs, recording YouTube lectures, designing an exam online, or requiring the use of proprietary software? Obviously, there are a myriad of great reasons, rationals, and benefits for all of the above, but the imperative to keep things simple, to use the right tech, to start with low tech interventions is to give teachers and students time and space to consider not just the how but the why of a tool or solution.

- Reasonable Accommodation and Universal Design: Overall, I think a just approach, when and where possible, is to think about the inclusion of digital technologies and tools in face-to-face and online classes in terms of reasonable accommodation and universal design. According to the American Psychological Association, reasonable accommodation is “reasonable adjustments or modifications to practices, policies and procedures, and to provide auxiliary aids and services for students with disabilities, unless to do so would ‘fundamentally alter’ the nature of the programs or result in an ‘undue burden.’ Providing accommodations do not compromise the essential elements of a course or curriculum; nor do they weaken the academic standards or integrity of a course. Accommodations simply provide an alternative way to accomplish the course requirements by eliminating or reducing disability-related barriers. They provide a level playing field, not an unfair advantage.” Universal design according to the Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology website is “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. UD is beneficial to all students, not just students with disabilities; for example, people who face challenges related to socioeconomic status, race, culture, gender, age, and language also benefit from UD practices.” Will the inclusion of a technology benefit the academic standards and integrity of the course? Will the technology be usable by everyone (as much as possible)? Will the technology be an undue burden to students, particularly those without easy access to computers, wifi, or specialized software? In other words, if the technology is integral to the course design, learning outcomes, and content (i.e. a class on multimodal composition or a class on computer-assisted design and engineering will necessitate the use of certain digital tools), then it is reasonable to require and include it. Moreover, where possible, how do we offer different routes and alternatives for students with legitimate reasons that cannot use or access the technology? In my games courses, for example, students are encouraged the play together (defraying cost or sharing equipment), to come to office hours to play on my computer (or if I am lucky enough to set up a lab computer on campus), or as a last resort, to watch a playthrough video of the game. I am clear, though, about the benefits and limitations of the above possibilities. Or, flipping the script, I do my best to provide everyone clear PDFs of all of the readings when possible as long as students have robust ways and practices for annotating and marking pages and passages. I still prefer students to read hardcopy when they can, but I do try to offer options particularly for students who are limited to reading on their phones even if it means making or lending copies of texts. While it is impossible to make everything universal, to reach all students, to make everyone happy, I do think having these ideals of accessibility and inclusive design strengthen courses for everyone involved.

Again, take everything with a grain of salt. Again, I hope this is illuminating and helpful. The more I dig into my own practices and pedagogies and assumptions, I am finding it harder and harder to corral everything into a neat list. But off the top of my head these are things that stand out as the most pressing, the most important, and sometimes the least discussed in online teaching.

Tomorrow, Rule #3: Wrangling Content.

Pingback: Ed’s Rules of Online Teaching, Part One: “Managing Expectations” – ED(MOND)CHANG(ED)AGOGY

Pingback: Ed’s Rules of Online Teaching, Addenda: Sample Stuff – ED(MOND)CHANG(ED)AGOGY

Pingback: Ed’s Rules of Online Teaching, Part Three: “Wrangling Content” – ED(MOND)CHANG(ED)AGOGY