Here are some things I have written, contributed to, and published. For more details, please refer to my full CV and online portfolio, which include my game designs and other projects.

“Fish, Roses, and Sexy Sutures: Disability, Embodied Estrangement, and Radical Care in Larissa Lai’s The Tiger Flu.” Co-authored with Stevi Costa. Project(ing) Human: Representations of Disability in Science Fiction. Ed. Courtney Stanton. Vernon Press. April 2023.

Elsa Sjunneson, editor of Uncanny Magazine’s Disabled People Destroy Science Fiction, further contends that science fiction replicates the curative imaginary, applying technological fixes to bodies in ways that carry ableist ideologies into the future. Our paper takes up Larissa Lai’s 2018 novel The Tiger Flu to argue that recent feminist and queer science fiction of color resist and reconfigure this “curative” and technological fix via the Grist Sisters, a rogue collective of female clones, who are trapped in the middle of a conflict between Isabelle Chow, the CEO of HOST Light Industries, and Marcus Traskin, the lord and CEO of the Pacific Pearl Parkade, both of whom seek to find a solution to the “tiger flu” pandemic. The Grist Sisters’ way of life imagines a different relationship to cure, one that envisions a future for disabled lives through “the sexy suture:” ritualized organ transplants provided by the village’s “starfish women,” whose bodies continually regenerate. Drawing on disability praxis, their social structure relies on a network of caregiving and caretaking in which the community provides critical life support for one another, complicating the curative imaginary from a queer crip feminist standpoint. All in all, The Tiger Flu is deeply critical of ableist mind/body dualism assumed by much of science fiction and upends the cyberpunk trope that treats the body as “meat” and the “prison of the mind” (a la William Gibson’s Neuromancer) and argues that hope and possibility, even in a dystopian world, is deeply embodied. By rejecting networked consciousness in favor of radical networks of activist community care, the novel allows readers, in the words of Raffaella Baccolini, to “see the differences of an elsewhere and thus think critically about the reader’s own world and possibly act on and change that world.”

“Playing Difference: Toward a Games of Color Pedagogy.” Co-authored with Ashlee Bird and Kishonna L. Gray. Critical Pedagogy, Race, and Media: Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education Teaching. Eds. Susan Flynn and Melanie Marotta. Routledge, December 2021.

In Gaming (2006), Alexander Galloway argues, “Video games render social realities into playable form” and “play is a symbolic action for larger issues in culture.” As gaming communities, industry, even scholars and teachers attempt to address the need for diversity and inclusion in games, how might we locate, include, theorize, and teach games of color and games that embrace difference? Specifically, how might we look at the representation and algorithmic underpinnings of racialized and marginalized identities, narratives, bodies, and cultures in games? In other words, as Gray and Leonard argue in the introduction of Woke Gaming, games are often problematically pedagogical in the naturalized ways they “provide opportunities to both learn and share the language of racism and sexism, and the grammar of empire, all while perpetuating cultures of violence and privilege.” This essay will offer practical interventions into these fraught languages, grammars, and algorithms in three parts: first, a definition and demonstration of close playing or critical ways of analyzing, engaging, and teaching games to address race and difference in digital games; next, three different approaches and assignments to teaching games of color; and finally, suggestions for developing a teaching with games philosophy. Kishonna L. Gray will address blackness and games through the example of Hair Nah (2017), a game about a black woman tired of people touching her hair; Ashlee Bird will discuss the importance of teaching the history of Indigenous representations in games and the teaching of the game Never Alone (2014); Edmond Y. Chang will look at games like Yellow Face (2019) to think through Asian American representation in games and Asianfuturism.

“Why Are the Digital Humanities So Straight?” Alternative Historiographies of the Digital Humanities. Ed. Dorothy Kim and Adeline Koh. Punctum Books, June 2021.

Building on Tara McPherson’s work on race, critical code studies, and feminist critiques of DH, which is provocatively condensed in her essay and question “Why Are the Digital Humanities So White?,” this non-traditional essay hopes to ask and address, “Why Are the Digital Humanities So Straight?” My essay and project, written as a BASIC program, will use the mediums of code and digital games to challenge the technonormativity of DH. In other words, is code “striaght” and is it possible to create a queer video game? Considering Kurt Squire’s argument that video games are “designed experiences,” this presentation takes up the problematic (im)possibility of queer games. Code and games in many ways are normative, structured, and deeply protocological even as gamers and game developers evince their promises of power, freedom, play, and agency. Alexander Galloway defines protocol as “a language that regulates flow, directs netspace, codes relationships, and connects life-forms” in ways that is “not by nature horizontal or vertical, but that protocol is an algorithm, a proscription for structure whose form and appearance may be any number of different diagrams or shapes.” My essay/program explores how the binary, algorithmic, and protocological underpinnings of both game programming and design constrain and recuperate queerness. Readers, coders, and players will be able to enter the BASIC essay/program in a BASIC emulator and run the essay/game.

“Queer.” Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments. Eds. Rebecca Frost Davis, Matthew Gold, Katherine D. Harris, and Jentery Sayers. Modern Language Association, March 2021. https://digitalpedagogy.hcommons.org/keyword/Queer.

What is queer digital pedagogy? What lies at the intersection and intertwingling of queer, technology, and teaching? Foremost, queer digital pedagogy understands that technology is never neutral and that the digital is a constellation of spaces, practices, and protocols that can be both liberatory and regulatory, both queer and deeply normative. Given the black-box-ness of code, computers, and information technologies, this playful and dissident work of decoding, remaking, and queering is needed across everyday screens, workbenches, classrooms, and society as a whole. Teachers, programmers, scholars, librarians, artists, and gamers must embrace “the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning” (Sedgwick 8) of queer digital pedagogy. Digital pedagogy must embrace a philosophy of teaching (with) technology that defies the desire for one-tool-fits-all solutions. There is no such thing as perfect communication, translation, or execution, but rather there are happy connections, coalitions, and conditions for experimentation and exploration.

“Drawing the Oankali: Imagining Race, Gender, and the Posthuman in Octavia Butler’s Dawn.” Approaches to Teaching the Works of Octavia E. Butler. Ed. Tarshia L. Stanley. Modern Language Association (MLA), August, 2019.

Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy imagines a post-apocalyptic Earth where humanity has been “saved” by the Oankali, an alien race with the ability to manipulate genetic material. Butler unflinchingly engages questions of race, gender, sexuality, power, and what it means to be human. Drawing on my courses that feature Butler’s trilogy, particularly Dawn, this chapter articulates the pedagogical opportunities raised by the Oankali. The essay focuses on a drawing assignment called “Imagining the Oankali” where students are asked to draw, represent, or create their idea of the aliens as a way to make visible how the novels dramatize difference, nonhumanness and posthumanness, and difficult identities and embodiments.

“Playing as Making.” Disrupting the Digital Humanities. Eds. Dorothy Kim and Jesse Stommel. Punctum Books. November 2018.

Johanna Drucker in “Humanistic Theory and Digital Scholarship” articulates as a key transformation (and bone of contention) in the variegated and interdisciplinary terrains of the digital humanities, saying, “I am trying to call for a next phase of digital humanities [that] synthesize method and theory into ways of doing as thinking…The challenge is to shift humanistic study from attention to the effects of technology…to a humanistically informed theory of the making of technology” (87). But what does it mean to do, to make? And what sorts of doing and making are privileged over others? In other words, what counts in this shift?

For some, digital humanities making comes down to code, programming, working in the back end. Stephen Ramsay has famously provoked, “Do you have to know how to code? I’m a tenured professor of digital humanities and I say ‘yes.’ So if you come to my program, you’re going to have to learn to do that eventually” (“Who’s In”). Like Drucker, Ramsay argues that digital humanities “involves moving from reading and critiquing to building and making…Media studies, game studies, critical code studies, and various other disciplines have brought wonderful new things to humanistic study, but I will say (at my peril) that none of these represent as radical a shift as the move from reading to making” (“On Building”). It is this foregrounding of doing and making that I want to take up, think about, and tinker with, not necessarily to rehash old debates or to pick (or pit) sides. Rather, I hope to articulate alternative modes and forms of doing that engage the modus operandi of making without depending on specialized or exclusionary barriers of entry. As Ramsay qualifies, “Personally, I think Digital Humanities is about building things. I’m willing to entertain highly expansive definitions of what it means to build something” (“Who’s In”). In other words, I hope to take advantage of and take for granted that doing, making, and building can and must include a range of practices, processes, and materialities, many of which are accessible, everyday, even vernacular. Specifically, I want to argue that playing a digital game is critical doing, that playing is making, and to embrace playing as making.

“A Game Chooses, A Player Obeys: BioShock, Posthumanism, and the Limits of Queerness.” Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games. Eds. Jennifer Malkowski and TreaAndrea M. Russworm. Indiana University Press, July 2017.

Recent years have seen an increase in public attention to identity and representation in video games, including journalists and bloggers holding the digital game industry accountable for the discrimination routinely endured by female gamers, queer gamers, and gamers of color. Video game developers are responding to these critiques, but scholarly discussion of representation in games has lagged far behind. Gaming Representation examines portrayals of race, gender, and sexuality in a range of games, from casuals like Diner Dash, to indies like Journey and The Binding of Isaac, to mainstream games from the Grand Theft Auto, BioShock, Spec Ops, The Last of Us, and Max Payne franchises. Arguing that representation and identity function as systems in games that share a stronger connection to code and platforms than it may first appear, the contributors to this volume push gaming scholarship to new levels of inquiry, theorizing, and imagination.

“Queergaming.” Queer Game Studies. Eds. Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw. University of Minnesota Press. March 2017.

Queergaming is a provocation, a call to games, a horizon of possibilities. Queergaming is a refusal of the idea that digital games and gaming communities are the sole provenance of adolescent, straight, white, cisgender, masculine, able, male, and “hardcore” bodies and desires and the articulation of and investment in alternative modes of play and ways of being. Queergaming is a challenge to this stereotypical, status quo intersection of game players, developers, cultures, and technologies, what I have elsewhere called the “technonormative matrix,” the digitized, gamified version of Judith Butler’s heteronormative matrix, “the matrix of power and discursive relations that effectively produce and regulate the intelligibility of [sex, gender, or sexuality] for us.” Ultimately, queergaming is heterogeneity of play, imagining different, even radical game narratives, interfaces, avatars, mechanics, soundscapes, programming, platforms, playerships, and communities. It is gaming’s changing present and necessary future.

“Love is in the Air: Queer (Im)possibility and Straightwashing in FrontierVille and World of Warcraft.” QED: A Journal of GLBTQ Worldmaking. Volume 2, Issue 2. Eds. Charles E. Morris III and Thomas K. Nakayama. June 2015.

Games like World of Warcraft have been called “inherently queer,” providing gamic spaces where gender and sexuality seem fluid and customizable. Although the provocation is exciting and revisits many of the arguments made about the liberatory potential of cyberspace, this article hopes to antidote the assumption that the virtual is “inherently” queer and to unpack what I call the “interactive fallacy,” the further assumption that video games offer players unlimited power and control. Through a close reading and close playing of two massively multiplayer games—Zynga’s casual game FrontierVille and Blizzard’s World of Warcraft—I hope to identify and interrogate the ways that gender and sexuality (even race) in games are both normative and subversive. In other words, in games about fantasy and fun, how and where and why might real world queerness, gender, and race be rendered, negotiated, and disrupted? Is that even possible? Games like FrontierVille and World of Warcraft offer beginnings for gendered and queered play, allowing players to imagine and enact a range of desires, but ultimately both games narrow these choices and possibilities, rendering them algorithmically inconsequential, and restore them to heteronormative ends. Looking at character creation, game play, and game narratives, this article argues for the productive opportunity in the play of, with, and play in sexuality and gender and race to discover what Lisa Nakamura calls “disruptive moments of recognition and misrecognition” that can offer subversive and queergaming potential and practices. Perhaps more important, this article also uncovers the ways that logics of digital games limit and norm players, narratives, and play itself.

“Teaching Harry Potter: Pedagogy as Play, Performance, and Textual Poaching.” Playing Harry Potter: Essays and Interviews on Fandom and Performance. Ed. Lisa Brenner. McFarland, 2015.

In the introduction to Reading Harry Potter, Giselle Liza Anatol argues, “The Potter series could become some of this generation’s most formative narratives, and it needs exploration and study rather than rejection as simply pulp, pop culture, or the latest fad.” This essay extends Anatol’s provocation by including the teaching of Harry Potter, particularly at the college level, pushing the engagement with Harry Potter beyond the more passive and personal activities of reading (and watching the films) to the performative and pedagogical practices of the classroom. Anatol continues, “Neglecting the potency of the novels and relegating them to the category of childhood trivia can result in the dangerously mistaken conclusions that the books do not reflect and/or comment upon the cultural assumptions and ideological tensions of contemporary society.” Drawing on the experience and execution of teaching Harry Potter courses at the University of Washington in Seattle, this essay hopes to articulate the critical potential and classroom challenges of using Harry Potter (and popular culture in general) to teach close reading, academic writing, critical thinking, and cultural analysis. Because the series navigates both fantasy and real world concerns, teaching Harry Potter offers ways to turn students’ passion for and engagement with the series into approaches to talking about race, gender, class, sexuality, and nation. In other words, this essay hopes to provide hands-on and practical ways to integrate Harry Potter into the classroom, allowing for collaborative play and collective performance, and ultimately, to theorize Harry Potter pedagogy as what Henry Jenkins calls “textual poaching,” a practice where fans transform their experience with a text or media into community and alternative ways of being.

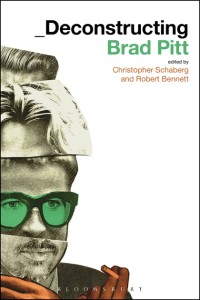

“Gay for Brad.” Deconstructing Brad Pitt. Eds. Christopher Schaberg and Robert Bennett. Bloomsbury, 2014.

“Who would you go gay for?” So asks the popular party game, truth- or- dare provocation. For self- identifi ed straight men, the answer more often than not is Brad Pitt. Brad Pitt with a healthy side of “if I had to choose,” and “I’m straight-as-an-arrow but,” and “no homo” qualifying. A cursory online search reveals the prevalence of this straight- male- pattern- gayness, or this “Brad Pitt Theory.” From star athletes to politicians to celebrity heartthrobs to everyday dudes, everyone seems all too willing to jump Brad Pitt’s bones. According to On Top magazine, pun intended, singer Robbie Williams would go gay for Brad for free even. House- beat- thumping, body rocking, booty shaking, self- identifi ed-49% homosexual, Williams says, “It’s 2 million pounds for Santa, but it’s a freebie for Brad Pitt.”But why specifically Pitt, and what bent logic makes men willingly heterofl exible? In other words, wherefore gay for Brad? Let us count the ways.

Read reviews of the edited collection: http://bloomsburyfilmandmedia.typepad.com/continuum_film_and_media/2014/09/of-actors-and-academics.html and http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/deconstructing-brad-pitt-9781623563967/

“Cards Against Humanity is __________.” First Person Scholar. March 17, 2015. Part of the special feature “Videogames, Queerness, & Beyond Dispatches from the 2014 Queerness & Games Conference.” Ed. Bonnie Ruberg. <http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/cards-against-humanity-is/>.

With this context in mind, I turn to Cards Against Humanity, which is a card game self-identified as “a party game for horrible people.” The game lets players match phrase cards (white cards) to a prompt card (black cards) and the goal is to produce the funniest, strangest, raunchiest, even most offensive response possible. The game was published and funded by a Kickstarter in January 2011. The Kickstarter video features cameos by the creators and writers of the game (who are predominantly white men), an explanation of how the game works, and also sets up the irreverent ethos of the game. What is interesting about the video is the ostensibly innocent notion that Cards Against Humanity is just about fun, getting together with your buddies to joke about funny things, and that what is funny and what is titillating is often based not just on unusual or strange pairings of prompt and answer but also humor based on things we know to be taboo, impolite, or patently offensive.

“Queer Dystopias, Queer Mechanics, and Queers in Love at the End of the World.” May 29, 2020 for In Media Res “Queerness in Games” week. In Media Res is a collaborative Media Commons project for online scholarship. Ed. Ashley Jones <http://mediacommons.org/imr/content/queer-dystopias-queer-mechanics-and-queers-love-end-world-0>.

Anna Anthropy’s game Queers in Love at the End of the World (2016) plays with the evanescence and ambivalence of queerness, time, erotics, and choice. One the surface, this Twine game is a quick series of hyperlinks narrating the last moments, parting words, and the final kisses and embraces of two lovers at the titular end of the world where and when “everything is wiped away.” However, what makes Queers in Love a queergame par excellence is its integration of a ten-second timer—a mechanic and temporality made queer—which transform both game and dystopian narrative into a critical queer dystopia.

“Pokemon Go, Queer Spaces, and Queer Contact.” October 15, 2016 for In Media Res “Pokemon Go” week. In Media Res is a collaborative Media Commons project for online scholarship. Ed. Colin Wheeler <http://mediacommons.org/imr/2016/10/15/pokemon-go-queer-spaces-and-queer-contact>.

Shortly after the release of Pokemon Go, stories of players’ accidental finds, mishaps, even dangerous encounters made headlines and social media feeds. One such story broke in July 2016 about players trolling the infamous anti-LGBT Westboro Baptist Church, which is a designated in-game Pokemon gym, with a cheerfully chubby and bright pink Clefairy named “LoveIsLove.” Beyond Poke-activism, there are numerous accounts of Pokemon Go-inspired friendships, meet-ups, sex, health benefits, and alternative fandoms. In other words, the mobile app and “augmented reality” game has become a catalyst for movement, behaviors, bodies, relationships, and shifts in public and private spaces all mediated by a digital game. Pokemon Go allows players to queer space, to repurpose ostensibly non-gamic places and geographies, and to engage in what Samuel Delany calls “queer contact” or the ways desire and intimacy often flows from chance encounters, particularly in metropolitan spaces, across race, class, gender, and sexuality.

“Better, Stronger, Faster? Bionic Woman and Posthuman Queerness.” January 23, 2015 for In Media Res “Post-human, Super-intelligent, Dream Girls” week. In Media Res is a collaborative Media Commons project for online scholarship. Ed. Jason Derby <http://mediacommons.org/imr/2015/01/07/better-stronger-faster-bionic-woman-and-posthuman-queerness>.

In 2007, NBC rebooted Bionic Woman with the promise that the show would be “Better. Stronger. Faster.” Starring Michelle Ryan as Jaime Sommers and Katee Sackhoff as Sarah Corvus, the prototype, Bionic Woman dramatizes the intersections of gender, technology, bodies, and heteronormativity. In the second episode, Jaime’s trainer Jae Kim says during their first session, “You think that just because you have machines inside you, that’s enough, that you’re invincible. The machine is nothing without the woman. We’re going beyond the demo…way beyond.” Though Jaime’s bionics allow her to run, jump, and fight, what the show imagines as possible through these technologies reveals the ways it presents and recuperates the posthuman body and hero(ine) back into normative femininity and ability.

“The Last Human: Doctor Who and Anxieties Over the Posthuman.” December 17, 2013 for In Media Res “Doctor Who” week. In Media Res is a collaborative Media Commons project for online scholarship. Ed. Lauren Cramer. <http://mediacommons.org/imr/2013/12/12/last-human-doctor-who-and-posthuman>.

“I am the last pure human!” so claims Lady Cassandra O’Brien.Δ17 in the second episode of the Doctor Who reboot. In the episode, “The End of the World,” the Doctor takes Rose on her first adventure: five billion years into the future where well-to-do beings have been invited to witness the destruction of Earth. One of the prominent guests is Lady Cassandra, who has become little more than a face and stretched skin. Interestingly, Cassandra’s claim relies on racial, genetic purity despite her extensive body modification. She rails, “The others mingled. Oh, they call themselves new humans and proto-humans and digi-humans—even human-ish. But you know what I call them? Mongrels!”

“‘Would You Kindly?’: Bioshock and Posthuman Choice.” Co-authored with Timothy Welsh. March 10, 2011 for In Media Res “Posthumanism and Media” week. Ed. Drew Ayers. <http://mediacommons.org/imr/2011/02/26/would-you-kindly>.

The video game Bioshock (Irrational Games, 2007) takes place in Rapture, an underwater utopian community modeled on the tenets of Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy. When the player-protagonist, Jack, arrives in Rapture, however, the city is near collapse after the introduction of biohacking technologies lead to an all-out civil war fought by genetically “enhanced” splicers. With this as its central conceit, Bioshock stages and disrupts self-determinist, laissez-faire ideology through and against posthumanism agency via the cyborg medium of video gaming.

“Alan Turing: The First Digital Humanist?” HASTAC Scholars Forum. Co-wrote and developed the forum prompt, organizing questions, and invited prominent academics and practitioners to participate in the public forum. Featured February 19-March 12, 2013. <http://hastac.org/forums/alan-turing-first-digital-humanist>.

Review of Chapter 12: “Roots and Revelation: Genetic Ancestry Testing and the YouTube Generation” by Alondra Nelson & Jeong Won Hwang. HASTAC Distributed Book Review of Race After the Internet (Edited by Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White). March 15, 2012. <http://hastac.org/blogs/fionab/2012/03/15/crowdsourced-book-review-race-after-internet>.

“Press Start to Continue: Toward a New Video Game Studies,” HASTAC Scholars Forum. Co-developed and wrote the forum prompt, organizing questions, and invited prominent academics and practitioners to participate in the public forum. Featured February 6-March 5, 2012. <http://hastac.org/forums/press-start-continue-toward-new-video-game-studies>.

Contributing Blogger for liberal.education nation. For the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) 2011 Annual Meeting in San Francisco, CA. January 2011.

- “Notes on the New Year, or, What the Cross Award Means to Me.” January 26, 2011.

- “Academic Glam.” January 28, 2011.

- “Imperfect Metaphors.” February 3, 2011.

“Gaming as Writing, Or, World of Warcraft as World of Wordcraft.” August/September 2008 for Computers and Composition Online special issue on “Reading Games: Composition, Literacy, and Video Gaming.” Eds. Richard Colby and Rebekah Shultz Colby. <http://cconlinejournal.org/gaming_issue_2008/Chang_Gaming_as_writing/index.html>.

In Gaming (2006), Alexander Galloway argues that “video games are actions” (p. 2), that video games “come into being when the machine is powered up and the software is executed; they exist when enacted” (p. 2). Might then this provide an opportunity to formulate a homology between gaming and writing? Might writing, in a sense, function as a kind of algorithm? The mind is powered up, critical thinking and language routines executed; writing only exists when enacted, when pen is put to paper, idea turned into word. For Galloway, gaming, playing, and acting invoke the language of writing: process, “grammars of action” (p. 4), diegetic and nondiegetic, and culture as acted document (p. 14). Moreover, gaming (like our students’ writing) does have stakes: “video games render social realities into playable form” (p. 17). Therefore, this webtext is a meditation, an exploration, and a invitation to understand the contours and ways gaming is like writing and depends on usable and teachable logics: narrative, close reading, critical analysis, and ultimately, play. Using the globally popular World of Warcraft, a massive multiplayer online role-playing game, this paper will render how gaming and writing are intellectual, analytical, and critical actions.

Again, for more details, please refer to my full CV and online portfolio, which include my game designs and other projects.